Robert’s maternal grandfather, Abraham Epstein Justman, emigrated from Tavrig, Lithuania in 1883 or 1884. We have no direct account of his experience but we do know that he became a peddler after he arrived in America. Later he had saved enough to buy a horse and cart so that he could sell fruit in Chicago. At one point he had saved enough money to help his daughter Dora to buy a house. In about 1885 he was able to bring his wife Mary and and children Dora and Jack to America. Robert’s mother, Kate, was born in Chicago. The history reproduced below is by David Epstein whom we are pretty sure was related to Abraham but we are not quite clear how.

Abraham was born with the surname Epstein but in America it became Sussman (meaning peddler) and was later changed to Justman.

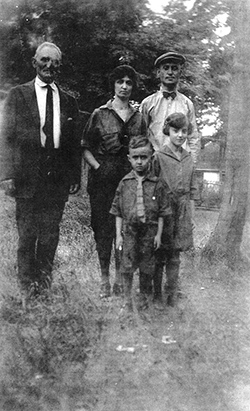

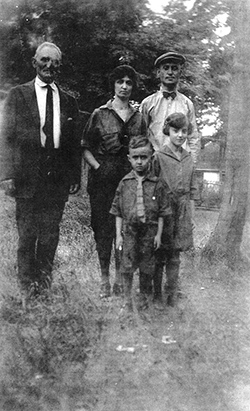

Wheeler?, Kate Bean, William Bean, Robert Bean, Millie Bean Dunlap

Mary Epstein Justman

The History of My Life

by David Epstein

I was born in the year of 1868 on the 8th day (last day) of Peisach in a town better know with the name as Tavrig, but the official name is Tauraggen (currently called Taurage), province of Kovno, Lithuania (under Russian rule then.) Tavrig was about a population of about 3,500 and about 99% Jewish. I was the oldest of 6 children, 3 boys and 3 girls, bom to my parents of their second marriage. My father had a daughter [Shewa?] from his first marriage and she died in her sixteenth year. My mother had 2 sons, Meier and Naftali, from her first marriage. Meier died in Paris, France in the year of 1935. Naftali and his family are living in New York City.

My brother Meier was raised in my uncle’s home in Devinsk (then Dinaburg)

Russia I only have a faint recollection of him when he once paid us a visit when he was in his late teens. I never saw him ever since, but we always kept up our correspondence until his very last days. He was a very sympathetic man, kind and good-hearted. While not any of my brothers and sisters ever saw him (except my youngest sister Ida), yet we all enjoyed him and loved him, which was brought on us just through his correspondence. In the year 1878 my brother Naftali left our home to join our brother Meier in Russian. We have never seen each other ever since, but we do keep up our corresponding at this day

Going back to my early childhood, infants used to be bandaged from the shoulders down Legs and arms bandaged together all in one. Only the head was moveable The rest of the body was stiff like a stick. After an infant was old enough to be nursed with food other than their mother’s milk, then the mother, or at times the hired maid, would chew up some food in their mouth to make it very fine, then take the food out of their mouth with their fingers and put it in the infant’s mouth. From that and many other unsanitary conditions, which I shall describe later, scores of infants did not survive, only but from a few months to a few years. Because there was no sewage at certain times of the years, conditions was so horrifying that I do not feel able to go into detail. I again can only wonder how people, especially children, survived as many as did. During the winter months we put in our doubled windows and filled up the cracks between the window frames and siding with cotton batts. No windows neither doors were ever left open from early fall until late in spring.

When I was in my fifth year I remember quite well how my mother wrapped me up in my father’s prayer shawl, grabbed me in her arms and with great enthusiasm and happiness carried me for about 2 blocks to Cheider (Hebrew School). It was a greatly achieved in life for a mother to take her son and present him to God, as the Cheider was to make a good Jew out of him Any good Jew who was able to read Hebrew and also translate into Yiddish, was well qualified to open a Cheider and there was many such Cheiders. The average Cheider had about 8 to 12 boys (girls was not supposed to attend any Cheider.) Cheider hours was from early in the morning until sundown in the summer, but in the winter it lasted until about 9 p m. Almost every year a child is changed to a different Cheider for no particular reasons, except that the father believed that his son will do better with another teacher. But the Cheider was actually a waste of time. It was only a place for the children to come together and play or visit with each other, without any system or discipline. The average boy would get a very little knowledge out of his whole Cheider life. Taking off a small percentage, the average Jew of that generation, had no knowledge of the meaning of the Hebrew words which they read and prayed three times daily.

Now lets go back to the inhabitants of Tavrig. While there was two classes of people financially, yet they were all wretchedly poor. About 2/3 of the inhabitants, while they managed to exist, yet they actually had no existence. While the rest barely existed, only about 1/2 dozen families who dealt with the outside world (meaning big cities in other provinces), they made a comfortable living.

My father probably belonged to the better off class. Why? Because he owned the house where we lived in, and also another house in our back yard which could accommodate two tenants, and we would rent it at $25.00 each per year. We also did rent a bedroom in the house where we lived ourselves for $25.00 per year, with free firewood and heat such as they were. We also owned a cow, which the barn joined on to the tenant’s house. Our house consists of a living room and a bedroom which was partitioned off from the living room. The partition was made of ordinary plain boards – not plastered or papered. And it did not reach to within about 18 inches of the ceiling, and as we also kept about a dozen chickens in the house, the top of the partition served as a roosting place for the chickens. There was also a kitchen, and off the kitchen another bedroom, which I mentioned that we did rent it out. The living room and our bedroom had a rough board floor, unmatched lumber, while the kitchen and the tenant’s room had a dirt floor.

Of course there was no gas, electric or any system of water works in that city or for that matter, none in any of the surrounding cites or towns. Therefore, any sanitary system was not even know to most of the inhabitants. Whenever our cow had to calf and if it would happen to be in the winter and on a severely cold night, then we would head the cow in the kitchen for over night. Then later we would keep the calf in the house until she was a week or 10 days old. In a corner of the kitchen stood an iron kettle of about 20 gallons for waste water and nearby a wooden barrel with fresh drinking water, where we did fill up with a bucket from a well in our back yard and where a dozen or more families would come to that well for drinking water. In my early childhood we also used to keep a maid, but in later years we could not afford one (although a maid used to work for just about board and room.)

My parents were bakers. They would bake large rye loaves of bread weighing about 10 to 15 lbs each. But on Friday, for Sabbath, they would bake Chaleh (white bread). Friday was my happy day which I used to look forward to, as I would get a white roll for breakfast, and 1/2 cup of milk, and only a half day for Cheider. Wheat bread was a delicacy as we only would get that on Sabbath. We lived on rye bread and potatoes 3 times daily. Butter? Almost none at all. Other dairy products? Only on very rare occasions. Meat or animal fat only once a week – on Sabbath day and also for the Friday night meal. Fruit of any kind was almost not known to us and vegetables we would get only on very rare occasions. The noon daily meal was usually, or I will rather say, most always potatoes boiled in jackets, and a small slice of salt herring (raw.) But as the funds was usually too low to buy a herring, we therefore used to get only the salty brine from the herring and dip the potatoes in it. Our desert after every meal was a glass of tea with a very small lump of sugar. From Sunday on, we would begin to look forward to the Sabbath, as we would wear our best clothes, such as they were. And the meal we would get on Friday night and again on Saturday noon? A meal that contained beef meat and white bread! Well, this was happiness in my childhood mind which I will never forget.

Family washing was done twice a year. The clothes was soaked in soap suds for a couple of days then boiled and taken over to the creek about 3/4 of a mile from our house, out of town. We would rinse it and slap it dry either on a wooden slab or stone, with a wooden slapper shaped and sized like a dust pan. The underwear was made out of home spun and home woven linen, and the stockings was home knitted. As the laundry was done once in six months, therefore everyone had to have a supply to change from once a week to perhaps once a month (according to their families’ ability and supply).

There was one public bath house in the city. Certain days were for males and certain days were for females. While there was a very small percentage who used to take baths weekly or some monthly, yet the average one took a bath twice yearly, and that was before Peisach and before the High Holidays. Home bathing was unknown as the accommodations was next to impossible. Conditions of this kind existed in all the surrounding town, and to the best of my knowledge, such conditions existed in all of Russia’s occupied countries and quite likely in Russia proper.

When I was about 10 years old, while still attending Cheider, my father sent me also to a school where it was taught arithmetic, and reading and writing Jewish and German. The better scholarly children took up also Russian, but very seldom made any headway with that. In that school is where I got my whatever education I possess now, equal to about 8th grade in America. In about my 14th year, I gave up other schools and attended an exclusive Russian school. Our teacher, who was a typical Russian, indulged in Vodka so much that, on the average, 2 days of every 5 school days he was dead drunk and we were told that the teacher was sick. But on the next year we had another teacher who could talk German That was much in favor with the pupils as the average student could understand just a very little Russian. The students were mostly Lithuanian from the nearby farms, just a few Russians, only 6 Jewish boys, and one girl. There was no other girl students. During the winter months, there was a bigger attendance of Lithuanian young men, all farmers’ sons. That school was a complete failure. I attended there for two years and everything that I got out of it (which was very little) was only through my own effort without any advise or instructions from the teacher. There was hardly any system and a student was hardly ever examined by the teacher.

Russian language was really to a very little use in our city, as it was thoroughly Germanized. Even in public and government places you could talk German. But if someone could speak only Russian, then they were last with the people at large as almost no one could understand him, and yet it was a Russian country and ruled by Russia.

There was a big open market place round in a circle in the center of the city with stores, shops, and saloons all around in a circle. Mondays and Thursdays of every week in the year, farmers brought to market all kinds of farm products, even from cattle to earthenware. Many farmers traveled with their horse and wagon a day and a night to come to market, while others from longer distances took 2 days, and 2 nights to reach the market place as going was very slow At certain times in the year the roads was deep with mud, while at other times they were solid, frozen, rough ground. Some of the city people too, had stands on the market place with the big loafs of rye bread, salt herring and many other homemade eatables My father, as a baker, looked forward to the market day in order to buy a supply of rye to last to the next market day. There was an express man who would pick up all the sacks of grain bought by bakers. He took the grain to the flour mill and returned the flour to the respective bakeries.

There was an incident in particular which happened and stamped in my mind in such a way that I still frequently think about it, and always did. One market day when I was about 7 or 8 years old, my father finds himself without funds to buy rye. I will never forget that sorrowful morning in our home. Though a child yet, I understood the depression and I carried the burden tremendously. Finally, early in the forenoon, but rather late for the market, my father sent me over to a friend and neighbor (Teive der Schindeluras) to borrow five dollars. Apparently he had no hope for success, but when I returned with the $5.00 in my hand, fathers eyes glowed up, saying “Oh, leben soil er” (meaning “God grant him long life”).

In my 15th year I got a job in a flour mill at $6.00 per month. My work was to weigh all grain brought in by the city bakers and farmers, and again to weigh the processed flour, minus a certain amount per 100 lbs On occasions, especially in the fall, farmers would come from long distances with big loads of grain. Quite often their grain wouldn’t be done into flour until past midnight, or until the early hours in the morning. I had to remain there until their flour was done and weighed in.

My home was about 1 1/2 miles from the mill. The city was always, in such hours, in total darkness and with dark, cloudy skys at that time of the year (in fall). There was no sidewalks, therefore, I walked about half way to my knees in mud and water. In those days, the average mind was trained to be superstitious. Mine was no different. About half the way to my home there was, in a corner, a Catholic Church. I knew that the homes’ of ghosts are in churches. There I always suspected to see ghosts or to hear them call my name I did not dare to turn around for fear that I may see one I kept going so fast, and with such a force, that I often used to think if I would run against a brick wall, I would have either blown my brains out or knocked over the brick wall.

I worked in that mill for about two years. Then the worries of my folks became what to with me to avoid me to go to the army. Them days, for parents to let their son go to the army was a terrible calamity. In fact, next to death, parents used to have their sons crippled in many ways, like loosing an eye, cutting off a finger or a toe, or having them drink poison as medicine, which in most cases ruined their health for life. My folks decided to send me to America.

I still remember my horrors when I had been told that I was to go to America! For me to cross the ocean! No! I wanted to die right there on the spot, and even should I by chance be lucky to get over the ocean, then for me to be in a strange land! I who never slept one night away from home. My life was embittered. Death would have been a relief, but preparations went on. My father had no funds, so they sold a small building adjoining our house – a kind of a barn where my grandfather (who was dead then) used to keep it as a hay office, selling hay by the pound. They sold the building for $50 00, which just about covered the entire passage from our city to Chicago, USA.

I was in my 17th year when the day arrived finally for me to bid my family good by forever and go to America. There was quite a few men in our city who owned a horse and wagon and who would take passengers to cross the Russian-German border. My father went with me to the German Border to see that I get over safe and away from the hold on me from the Russian Czar. But things don’t always run smooth. The immigration officers find my passport illegal. I had a chance to be under arrest right there, but for some reason they did not, so father took me back home. The fear of that following night was terrible, as we looked every minute for soldiers to come and put me and father under arrest and take us away.

On the next day, mother took out a pass for her and myself to cross the border into Germany. This time somehow, they again became suspicious. The Russian officers were very suspicious of Jews and were looking for bribes, so they took me in a separate room to question me. Apparently my answers must have been satisfactory as they let us pass Mother was happy I could not say that on myself.

Anyhow, I was out of the clutches of the Czar. I was in Germany and I was free! My mother went along with me to Tilsit, a city which was several hours drive from the border Along late in the afternoon, the same man with his horse and wagon who brought us, took mother back home. I will never forget the time when the wagon with my mother in it began to move away from me. Mother constantly kept turning back and wave her hand at me. Finally, I heard her cry hysterically. Her cry rang in my ears all of that day and many days after. Yes, I can hear her cry at this day whenever I think about it. Apparently her heart told her that she will never see me again. My thoughts were different. I quite well knew that I am going to America to make money. Then, I would return home to my father and mother. Would I then have known that I would never return home, I would collapse on the spot But that was the last of seeing my father and mother.

My ticket was arranged for transportation from here on to Chicago. So the office of the Company where my ticket was bought took me in a sort of a truck wagon with about a dozen men or more in it to an immigration house where we were to stay there all night On the next day we were to take a train to Hamburg, a port city. That night in the immigration house was a terrible night for me. They took me in a room to sleep where there was about two dozen men and they all looked like the very poor laboring class And they talked a language which I could not understand (probably Hungarian). We slept three in a bed. I went to bed with all my clothes on, boots, cap and all. So did all the others. They kept on jabbering away while in bed I was scared stiff, and tired, and most of all, very lonesome. We arrived in Hamburg on the following day along in the afternoon It was on a Friday. We went on board the liner toward evening. I felt terrible that I had to start sailing on the Sabbath. This was my first commitment against my Jewishness. That sin laid heavy on my heart.

Late in the evening our ship began to move and along about midnight, we were in terrific stormy waters. My baggage which was contained in a homemade wooden box, had been sliding back and forth all over the cabin (so did others). I began to be sick and so did everyone in the cabin. I felt that we are going to get drowned and I lay it to my sin of breaking the Sabbath rule. Yes, I felt this was the end. But it was not, as in the early morning hours the ocean was calm and from a distance we began to see land I thought we were in the mid ocean, but the fact was that we had only crossed the English Channel and in the morning we arrived in Liverpool, England

I sure felt like a new bom boy, with a new lease on life. It was a bright sunshiny morning as we were nearing the city. Crowds of people stood there at the edge watching the ship arrive. I was just horrified with surprise when I saw a black man amongst the crowd, the first colored man I had ever seen in my life. If my recollection now is right, I think that then, I had never known or heard that there was any such things in existence as black human beings.

We stayed in Liverpool for about seven days, waiting for a liner. I must say that I did not dislike my stay in Liverpool as the food we got was considerably better than at home, especially the sugar on the table. It was free for anyone to help themselves all they want, and I was one who took the advantage as I was very sugar hungry, and at home sugar was very precious and, therefore, very sparingly used. Yes, Liverpool was an enchanted city to me – a new world – as everything was a curiosity to me. Houses, sidewalk, street cars, double-decker busses drawn by two horses was the most novel to me and it took me a long time to understand what this is all about. Yes, even people and their dress was different to me. You can not imagine my curiosity seeing women carrying baskets on their heads filled with oranges and bananas, selling to the new arrivals. I never know that loads could be carried on one’s head, especially women’s. Bananas was an unknown fruit to me, I never saw it. Oranges was a very precious fruit with me as I had never ate an orange, but just had a little taste of it as oranges is only bought to give to the sick, and they only got just a taste. A whole orange was made to last several days, as oranges was scarce and rather very expensive. And here I see where people are eating them as if they would have been as common as potatoes. That, too, was a wonder to me I did not dare to buy because I was afraid they would cost too much and I will find myself without money before I got to Chicago.

Finally a ship has arrived to take me to America. It was a very stormy five-week voyage to America. I was sea-sick practically every day. One morning news spread in our cabin that land is visible The ocean was calm. Therefore we were able to come up on the deck in the sunshine (sunshine was very rare during my voyage) and watch the land at a far distance. I felt happy to watch the land coming closer and closer to us. We finally landed in Philadelphia I then felt like a new bom boy. I am on land and in America!

Getting off the ship, I was put in the train and off to Chicago. I arrived in Chicago one bright sunshiny morning. I went off the train, and out from the big depot on to the street My next thought was “where do I turn?” I had in my pocket an address of a boy friend of mine who has been in America for about a year and who had been living with his mother, or shall I rather say that his mother lived with him. I could not talk neither understand a word in English, so I had to show my piece of paper with the address of my friend and people gave me to understand or motioned the direction where I was to go. So I set about to my destination. I was able to read the names of streets which was printed on the street corner lanterns, of course. I kept showing my slip of paper to people every now and then. Finally I reached my street. Then my job was to find the house number, which I felt I could do without asking I tracked down my number and anyone can hardly imagine the joy to have found my people that I knew, They too had a big surprise to see me.

My first thought was to write a letter to my mother and father, but I had no money to buy a postage stamp as I only had $0.25 in my whole possession and they told me that I will have to pay that amount in the depot for keeping my box in the baggage room. On the next following morning I went back to the depot and got my only box and carried it on my shoulder to my new home. Then right after breakfast my friend offered to loan me a dollar and he took me to a wholesale store where they were selling matches, so I bought a market basket and matches, and went out on the street selling matches. Of course I had to study up the American coins, which it was all strange to me. They charged me 80 cents per week for room, tea and sugar, all I wanted. The Friday night meal and the Sabbath noon meal were included. All other meals was on my own. My menu was rye bread and tea for desert. That one pound of bread did cost 5 cents and I managed to have it for two meals, but I could easily have eaten all of it at one meal.

I had struggled along selling matches on the Chicago streets for several weeks and barely earned my room and board. A landsman of mine, a man who came from the same town where I was from and who knew my parents but never knew, neither saw me, heard that I had arrived in Chicago (those days, names of new arrivals, or greenhorns as we have been called, used to spread quickly amongst our Landslite). So that above mentioned countryman of mine called on me and offered me to loan me a stock of merchandise if I would come along with him to Lake Zurich, Illinois about 40 miles northwest of Chicago where he was running a small country general merchandise store, and I should peddle goods amongst farmers, but buy merchandise of him. I certainly grabbed the opportunity and went out peddling amongst the farmers.

My life as a peddler was not very sweet. First of all, I was the most homesick boy anyone can imagine. I’d be walking along on the country road, from farm house to farm house and would cry my heart out while on my way. My load on my back, with a valise on my chest was often twice the weight of myself. When night would overtake me I was not always lucky to be granted my request to let me stay overnight. There was no paved roads anywheres them days, and one particular afternoon, in the fall of the year, when it had rained steadily and when darkness overtook me, farm houses was far apart one from another and by the time I arrived to the farm house it was quite dark. My request to stay all night was not granted, so I had to walk about a mile in deep mud to my ankles with my heavy pack on my back to the next farmhouse The dog gave the alarm that someone is near The Farmer opened the door and tamed the dog until I arrived to the house. That farmer luckily took me in, befriended me, and served me a supper (of course it was after supper with the family). I was about starved, but I forgot about hunger as my great worry was where to stay overnight. Therefore, anyone can hardly imagine the comfort and appreciation I felt knowing that I have a roof over my head and a bed to sleep in. The world was my own and I have forgotten all my troubles, but at the end of the next day, the same worry started over again. So I lived a life like that for about 1 1/2 years, which by degrees it gradually changed for the better, as I began to understand some English words and was able to answer. Besides I begin to get acquainted with the farmers, which I used to make my regular calls every so often. They learned to know me while I learned to know them until I finally established homes in all my territory wherever I peddled. But my troubles has not been over as my homesickness did not let up a bit. Many times each day while walking by the wayside I lowered my pack to the ground, sat down to rest, and cried, often times for an hour steady. I prayed to God to send the angel of death to take me Death would have been welcome as I did not want to live.

I have been brought up in my parents home to be very pious and a very pious boy I sure was I was brought up to read the morning services every day in my prayer book and I never missed it even under very bad inconveniences – living for years with Gentiles and not being willing to let them know that I was praying. My praying always had to be done before breakfast, therefore it was not easy to do it in hiding. I would have felt very embarrassed if I would have been caught praying. But it happened! One particular morning during a real cold spell of severe zero weather, the farmer was ready to drive to the milk factory that delivered his milk but he needed mittens and other clothes. So early in the morning they called me to open my pack. That morning the farmer and his family bought considerable merchandise. Breakfast was served at the table but I had not yet read my prayers and the whole family waited for me to close my pack and sit down to eat. I sat down and food was passed over to me. I felt like being in hot water. How can I eat? My prayers has not been read! My conscious has been revolting in me. I carried a spoon-full of food to my mouth. I swallowed I felt that something like thunder will strike me and kill me instantly I turned right and left I looked around, but nothing has struck me! I was very much surprised why nothing has happened! I wondered why? Well, such instances happened again and again and again, but every time with a feeling of less and less fear of committing a crime.

After three long and very unpleasant years of peddling, I made money enough to buy an old worn out horse and a buggy which had seen better days I felt big – that I did not have to carry my pack on my back – and my customers thought that peddling is a very profitable business. After putting in nine more years of my young life peddling, I began to realize that work of that kind was no life and no future. I gave up peddling, come to Chicago and just had money enough to pay the price to one who owned a candy and cigar store with hardly any stock in it. I managed to hold out in that store for about two years and at the end I came very near loosing all I saved by peddling.

Simon Epstein! A boy of about my age and whom I knew, or we knew each other, as small children in our home town (and as you see, my namesake, too). He, too, went through a life about the same as my own and with the same misfortune in his store, which he has conducted in Chicago. We came together and talked over our future. We both agreed that with the very little we had left and with the little credit we had at the wholesale stores where we used to buy goods while peddlers, we would start a store in Antioch, Illinois, a small country town, where the farmers surrounding the town knew us. We lived there about 3 1/2 years and managed to save enough to start a store with a little bigger stock and decided to move to Carystation, Illinois. Here we also felt like at home as the farmers for miles around know us from our peddling years. After 3 1/2 years in Carystation, we felt that we are able to establish ourselves in a bigger town and with a bigger stock of goods. So in the year of 1897, we choose Delavan, Wisconsin to establish our place of business. After two years we felt that we are able to get married and support our wives.

As it was customary to visit new arrivals from Europe, especially one from one’s own town, I went to visit Eda Epstein at her step sister’s home with whom she was living While I was sitting in the living room, there was a slim girl of about fifteen years of age running in barefooted on the bare wooden floor of the room, and quickly running out She appeared to be busy and had no time to stay. As I knew everyone in the family, I therefore knew that this strange girl was the new arrival. Although she was born and raised only a few blocks away on the same street where I lived, but I never saw her. In later years she told me that she knew me, as she used to see me near my home on several occasions.

I never had any introduction taken on my first visit at her new adopted home, but later on in years, I meet her rarely now and then. One day I asked her whether she would want me to take her to my sister’s wedding. She accepted the invitation without hesitating. I went to the nearest livery stable from where I lived and hired a carriage with two horses and a coachman. I directed the coachman to take me to the home of Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs, an Uncle and Aunt of Eda with whom she then made her home. It was rather a very showy affair and a pride for any young girl for a rig of that kind to await her at her door. We went to a neighborhood temple where my sister’s wedding took place. We found there a good sized crowd. After the ceremony there were music and dancing. As I never knew how to dance, therefore I could not entertain Eda to good advantage. But as the crowd were all Landslitee (all from the same town in Europe) therefore everybody knew everybody and everybody had a good time and kept busy. During the whole evening, Eda and myself were a very little together and did not have much to say to each other. At a late hour we parted. I did not take Eda home. Whether it was through my stupidity or just common ordinary custom, I don’t know, but I have arranged with some girls who went her way to see her home. And as I lived a long distance away, I went alone home on a streetcar.

My date with Eda, I believe, was the first step nearer toward a possible proposal, yet for the next several years we have seen a very little of each other But when her brother, Simon, became my partner in business, then Eda used to come to spend her vacation out in the country to be with us. That was when we had a chance to learn more of each other.The proposal I believe came out from the mouth of both of us at the same time. We then set a date for our wedding and it was to be on a Sunday.

That Saturday before our wedding day, was a very busy day in the store, and as stores used to be kept open very late, especially on Saturday evenings, we therefore retired on about past midnight. But as there was only one train going to Chicago on Sunday, and it was early in the morning, we therefore was afraid that we may oversleep, so we set many alarm clocks all to ring at the same time, but we were up in the morning before the time for the clocks to ring and we met our train.

I forgot to mention that Simon too, set his wedding day at the same date so we can have a double wedding at the same time So we got to Chicago where we meet our brides. Everything has been set and arranged for the doubled wedding at the home of Mr and Mrs. Jacobs (the future inlaws of Simon). After the wedding dinner we took our brides to the train with us and back to Delavan, Wisconsin. We had our homes ready and furnished completely. I was a married man! And it was the first home Eda and I ever had since we left our parents home. Regardless how humble, we appreciated our home. We were both happy. But a humble home it surely was. It had no home conveniences whatsoever. There was no running water, no kitchen sink, no outlet of waste water Of course electricity and gas was not known in our city, neither in any of all the surrounding cities.

Two daughters were bom to us in the first home of ours. With two babies, Eda had her hands full with work as we had to bring in every bit of water form the street near the next door neighbor and carry out every bit of waste water During the winter months while the days were short and the weather subzero with plenty of snow and ice, on wash days Eda and myself used to get up on about 3 am to do the washing. Why that early? Because I had to leave for the store at 7 am and would have had no time to help Eda with the children and washing during the day. Eda was not able to bring in the water from the street, where all around the well was about 2 feet thick with frozen ice and very slippery, and then carry out all the waste water. So by the time I left for the store in the morning the washing was ready for the line.

Eda had to manufacturer much of the food we ate. She baked all of her bread and pies, made preserves and did all the cooking and canning too. She did a lot of serving both for the babies and herself and she find time to do considerable embroidering and crocheting. We lived in that home for about 3 years, then we moved to a much handier home with much more comfort. Our life in Delavan was very pleasant, and in a way we felt financially successful too and yet, it felt rather lonesome as by nature we were rather bashful or shall I rather say as we were no mixture. We therefore was lacking social companionship.

Our girls began to be grown up. They graduated from Delavan High School, as well as of the University of Wisconsin. They have not been much at home then, and that added up more loneliness to the home especially to their mother. We then began to give our thought to retire from business and move to Chicago (to the home of Eda’s girlhood, where she kept up a lot of friends and relatives) with the hope that life will be more interesting. So, after living in Delavan, Wisconsin for 25 years, we gave up our business and moved to Chicago in the spring of 1922. The first summer being idle has not been to my liking. Along towards fall, I hunt my self up a job in a Downtown department store selling shoes, having in mind to work just through the Holidays, but I worked in that store for 65 [?] years steady. During that time both of our daughters were married. So my wife and myself decided to take a trip to California. We have been away for 9 months on that trip visiting in various interesting places. Then we returned back to Chicago. It was then in 1929 and just when the Depression started all through the country. Needless to say that we two got our share of it.

Our daughter Ethel and her husband Nate were then both working. We therefore decided to rent an apartment for both of our families to live together. After about 6 years living together, then Marilyn our grand daughter was born to Ethel and Nate. Our daughter Janet who then lived in California invited us to come to spend some time with her, so we gave up our household and moved to California. We liked California real well So we decided to make our permanent home in this state and chose Los Angeles. We are living in L A. now for about 9 years and feel quite content Last spring it was 50 years since Eda and I were married.

We have been invited by our daughter Ethel and her husband Nate to come and celebrate our gold wedding anniversary at their home in Highland Park, Illinois. Our daughter Janet, who now lives in New York City, came to be with us during the celebration. The 18th of June was set for the day and what a day it was!!! There was about 45 guests, all of our own family, and each and everyone had a wonderful time. It sure was most exciting and the happiest day of our lives We are now back to our home in LA. I am 81 years of age My wife Eda is 76 years of age. We are content and feel grateful to the Almighty that we can live independent all on our own at our age as we are now.

Here is a prayer in Hebrew which we read in atonement day, “A1 Tashlicheinu Lei- eiss Ziknoh Kichlaus Kaucheinual Taazweinu” (Do not desert us at our old age when our strength and health are at exhaustion.)

David L. Epstein, 1949